Ballistic vs. Plyometric: Understanding Dynamic Movements

TOPIC: Strength & Conditioning

Fred Ormerod is a freelance coach, army reserve medic, nurse, master’s student, and massage therapist. He’s spent a decade working in healthcare and five years coaching in one of Edinburgh’s leading training facilities.

Written By

fred ormerod

Fred Ormerod is a freelance coach, army reserve medic, nurse, master’s student, and massage therapist. He’s spent a decade working in healthcare and five years coaching in one of Edinburgh’s leading training facilities.

Website

Programs

What Are Plyometrics?

Plyometrics are exercises that stimulate the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC). There are two elements to this:

- Elastic elements (fascia and tendons)

- Contractile (muscle) element

Imagine the human body is a mattress spring (or Hookian spring if you’re into physics) — if you compress it or stretch it, the spring will recoil back, just like when we perform a jump. During this jump we have three phases which you might have heard of:

- The eccentric phase – where the spring stretches (think EE-longate), this is the downward motion of a jump as we load or ‘pre-stretch’ the muscles

- The amortization phase – the brief period between phases, don’t worry about this one, I never do.

- The concentric phase – where the spring CON-tracts, or we jump.

The two elements combine in these three phases to produce a force at a certain speed. The harder the muscles pull on the elastic elements the greater the force, they can also contract faster or slower, and this is influenced by how elastic or stiff the other elements are.

Why Should You Jump?

As athletes it is important to improve upon this elastic recoil in our training. Running faster, jumping further and hitting harder are all good enough reasons for this.

As you’d expect, improvements can be found by increasing the size of muscles (contractile), tendons (elastic) and absolute contractile force through simple strength training. However, we want to get really explosive and fast in our training/sport and doing so can help reduce the risk of many common injuries as well.

The Strength-Speed Curve

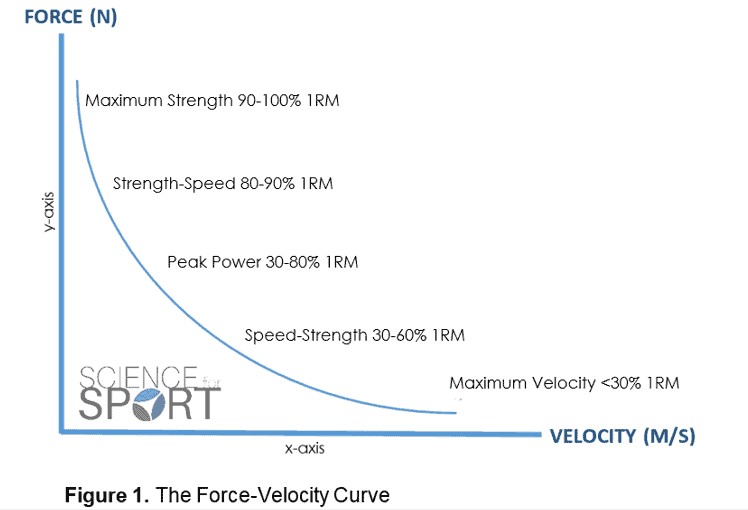

There is a spectrum of stimuli you can glean from training movements under different loads and at different speeds. Depending on your needs as an athlete, it’s wise to train specifically for that need. For instance, if you’re a powerlifter, you might want to focus primarily on the strength, maybe strength-speed portion of the curve. If you’re a ballet dancer or a fancy, flying, foot-working footballer, the speed-strength end of the curve might be more prominent in your training.

The strength-speed curve above details what zones you might want to train in for your specific purposes, once you’re sure you need to. A lot of athletes should aim to live in the middle unless you are sport-specified.

It is worth bearing in mind that your power output will always be limited by your maximum strength output. As such, you might be better spending your time simply getting stronger. As a rough guide, if you’re unable to squat or deadlift your body weight and bench press at least 75% of your bodyweight, then it’s a good idea to improve upon that before you spend too many hours of your training week on any of the ballistic/plyometric movements detailed here.

In fact, if you don’t see improvements in your ballistic outputs after training with these movements for an extended period (i.e. you can’t throw or jump further or faster than before) it’s likely because you’re limited by strength rather than the ability to perform movements quickly.

Assuming you’re strong enough to warrant including ballistic or plyometric training (and it’s worth getting help in continually assessing this) let’s have a look at what this training can do for you.

What is Ballistic Training?

Dynamic jumping movements are divided into two categories to avoid confusion and put each to their proper use. These are long (ballistic) and short (plyometric) response exercises.

Ballistic training is high velocity (fast moving) often with maximum (or close to) intent. The purpose of which is to build strength-speed in athletes.

There are multiple benefits in sports for training ballistic movements:

- Muscle hypertrophy (mostly in people new to training)

- Increased muscle fiber contraction force

- Improved muscle contraction speed

All of which tend to lead to improved performance in training tests, strength tests and competition performance.

What is Plyometric Training?

Plyo work involves high velocity training with typically lower loads. They’re usually programmed to help improve speed-strength and reactive strength in athletes. The key element is fast contraction speed. What you’re looking for is a fast change from eccentric to concentric movements. Some scientists go so far as to classify plyometric contraction as anything below 0.25 seconds and the stimuli you gain from performing them regularly differ slightly to ballistic movements:

- Increased tendon elasticity

- Increased tendon stiffness

- Reduced time for eccentric loading in jumping movements and in change of direction (you can jump and change direction faster without having to ‘pre-stretch’ muscles as much)

- Reduced risk of injury due to increased tendon strength and stiffness

You might find that some jumps you do are ballistic in nature; you dip into them slower and jump further. Others are plyometric; you dip down as fast as possible so the muscles and tendons don’t have the same elastic recoil and you don’t jump as far (but you might change direction quicker).

| Examples of ballistic movements | Examples of plyometric movements |

| Box jump Countermovement jump Medicine ball throw Ballistic bench press ‘plyo’ push up Olympic lifts/derivatives Lateral bounds Kettlebell swings Depth jump (for height) |

Light hang cleans Stiff legged pogo jumps (perhaps assisted with a band) AFSM exercises (give them a look on Youtube) Skipping Punching drills Catching drills Footwork drills Stiff legged depth jump (for speed) |

How Do I Program Plyometrics & Ballistics?

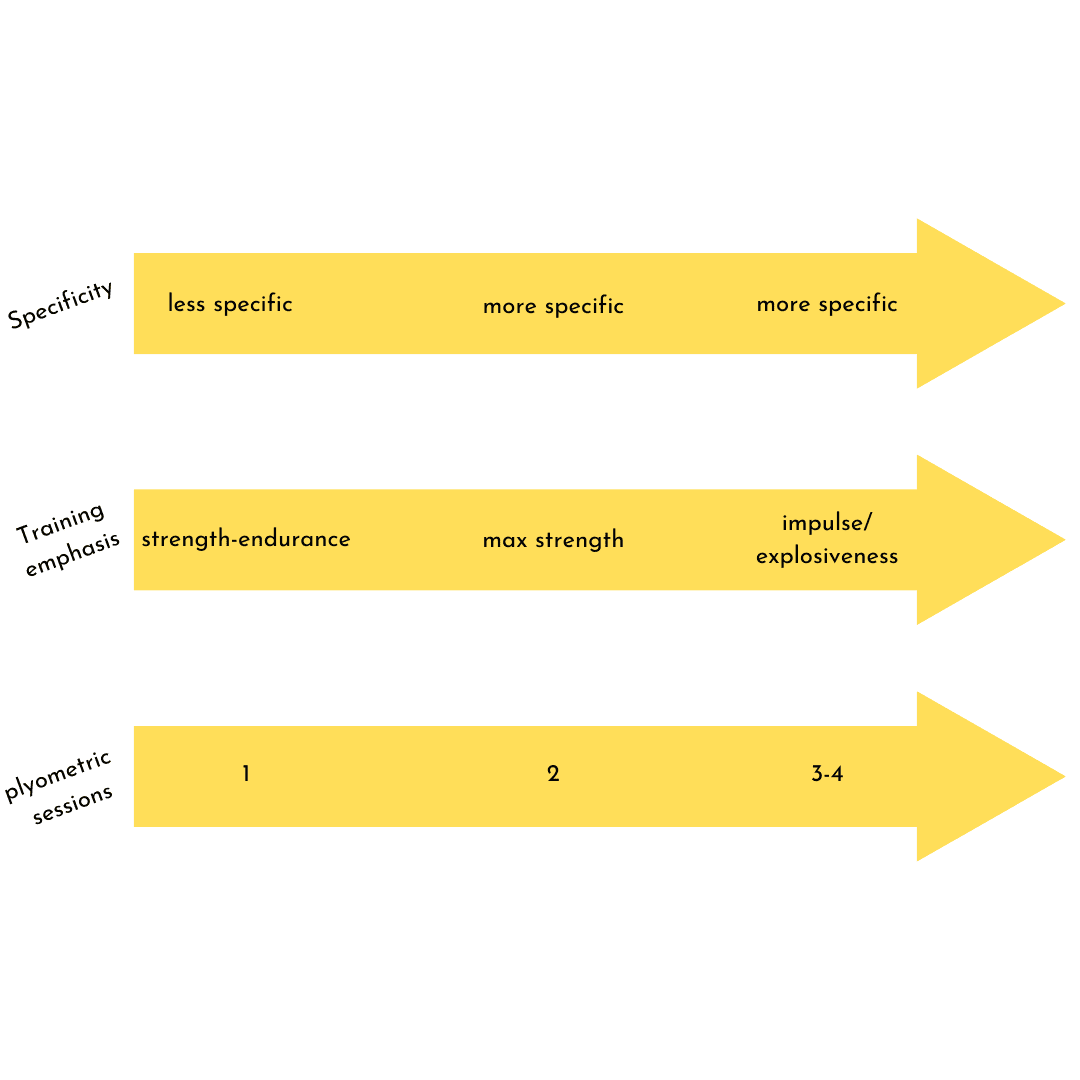

Proper periodization is very important. Below you’ll find a table highlighting how much plyometric work to include in your training at different stages of a training plan:

It’s generally suggested that you should have 48-72 hours between intense plyometric training sessions, meaning about 2-3 times per week depending on your schedule.

It’s worth considering how many contacts you absorb per training week since introducing high volume can lead to severe delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) and even tendonitis. Starting out at 80-100 contacts per week and building to 120-140 as you progress is advised. You’d do well to include any sport specific training into this count as well. I’ve learned this from experience in coaching elite fencers who absorb hundreds of contacts through their lead leg and do not need extra intense training sessions during which they absorb more force.

If you’d like to learn more about a plyometric training plan specific to your needs feel free to drop me a message on instagram @fred.strengthcoach or check out my max power BJJ plan — a full 12-week training program designed to increase athletes’ speed, strength and power.

Find Your Perfect Training Plan

Sometimes all you need to reach your destination on your fitness journey is an expert guide. Look no further, we've got you covered. Browse from thousands of programs for any goal and every type of athlete.

Try any programming subscription FREE for 7 days!

Related Articles

You May Also Like...

32 & Lifting: Reflections on My First Powerlifting Competition

Stepping onto the powerlifting platform at 32, just 13 months post-ACL surgery, Fred Ormerod chronicles his return to competitive sports after a 14-year hiatus. From shedding over 15kg to meet weight class requirements to confronting self-doubt and embracing the...

Intermittent Fasting for Shift-Working Athletes

Shift work can make fueling for performance feel like a constant battle. Between erratic schedules, disrupted sleep, and unpredictable training windows, sticking to a nutrition plan can be tough. Intermittent fasting (IF) offers a flexible approach that may already...

The Ultimate Low Back Training Guide: Tips for a Stronger Spine

Low back pain sidelines countless athletes and gym-goers. But here’s the truth: your lower back doesn’t need endless isolation work to stay strong. The real secret? A smart mix of direct and indirect training strategies. This guide breaks it all down, giving you...

32 & Lifting: Reflections on My First Powerlifting Competition

Stepping onto the powerlifting platform at 32, just 13 months post-ACL surgery, Fred Ormerod chronicles his return to competitive sports after a 14-year hiatus. From shedding over 15kg to meet weight class requirements to confronting self-doubt and embracing the...

Intermittent Fasting for Shift-Working Athletes

Shift work can make fueling for performance feel like a constant battle. Between erratic schedules, disrupted sleep, and unpredictable training windows, sticking to a nutrition plan can be tough. Intermittent fasting (IF) offers a flexible approach that may already...

Want more training content?

Subscribe

For Coaches

For Athletes

About

Support

Training Lab

Access the latest articles, reviews, and case studies from the top strength and conditioning minds in the TH Training Lab!

Made with love, sweat, protein isolate and hard work in Denver, CO

© 2024 TrainHeroic, Inc. All rights reserved.