How to Build a Better Strength Training Program

Sports Performance | Strength & ConditioningABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Andy Galpin

Dr. Andy Galpin is a Professor of Kinesiology at the Center for Sport Performance at California State University, Fullerton. Andy has a Ph.D. in Human Bioenergetics and is the founder and director of the Biochemistry and Molecular Exercise Laboratory. He’s the co-author of Unplugged with Brian Mackenzie and Phil White. In addition, he co-hosts the Body of Knowledge podcast. Learn more at www.andygalpin.com

// 7 Variables to Improve Your Athletes’ Strength Training Program

There are many ways to advance your coaching craft, from working on communication to studying the latest methods to learning how to better evaluate outcomes. Yet one of the simplest and most effective things you can do to benefit your craft and your athletes is to learn how to create solid strength training programs. In this article, I’ll walk you through seven variables you can use to establish and execute better strength training, no matter what sports your athletes compete in and which populations you serve.

Before we jump into our main topic though, there are two steps you should take. The first is a needs analysis to determine what you’re actually training your athletes for. From there, you should set some main goals. Next, you can move onto creating a strength training program or modifying an existing one by tweaking the variables below.

Your Title Goes Here

Your content goes here. Edit or remove this text inline or in the module Content settings. You can also style every aspect of this content in the module Design settings and even apply custom CSS to this text in the module Advanced settings.

1. Choice

You’ve determined you want a certain adaptation for your athletes. Now it’s time to choose the exercises in such a manner that there’s a high likelihood of them achieving this and reaching their goals. Remember that exercises themselves do NOT guarantee a certain adaptation. You can’t simply say, “I want my athletes to get stronger, so I’m going to have them deadlift because that’s the best lift for strength.” Not so! Exercises don’t determine adaptations – how you perform them does. This involves some of the variables we’ll explore in a moment like intensity and rest, as well as rep ranges, technique, and so on. In other words, it’s the application that really matters.

That said, exercise choice does determine certain things. These include movement plane, the muscles and joints you’re using, the type of muscle contractions (concentric, eccentric, and isometric), and technical proficiency. So these are factors to take into account when considering whether to include a certain exercise in your program or not. Others include the goal of the sport/activity, energy system (s), if it’s sport-specific or not, injury history and status, anthropometrics, exercise progression/regression (based on the athlete’s experience and competence), mobility/flexibility, the need for variation, and balancing being idealistic and realistic.

2. Order

We’re talking about exercise order today, not across an entire program. You should do the fastest things first – speed, then power, then strength, then hypertrophy, then conditioning/endurance. This isn’t some arbitrary sequence I came up with. If you do the inverse, you’ll reduce your speed, won’t be as strong, and will be less powerful. Forget misguided notions about mindset or mental toughness here. What we’re talking about is how to program optimally from a physiological standpoint. Performing conditioning exercises first will make you more tired and reduce the benefit of subsequent speed, power, and strength.

The inverse isn’t the same: putting speed first doesn’t have a detrimental effect on conditioning, nor does putting power exercises before those targeting hypertrophy compromise the latter. Another thing to consider is the possibility of injury. Imagine you ask an athlete to do a high rep push-up and pull-up circuit for time with high reps. Now their shoulder muscles are fatigued, and you get them to do heavy overhead presses explosively. They’re at far greater risk of getting hurt than if they’d done their power and strength work before that circuit. So save your hypertrophy, conditioning, and endurance for last.

3. Frequency

We could apply this term in several ways, but for the sake of simplicity let’s just make it the answer to the question, “How many times a week are you training?” It’s not uncommon for some of the MMA guys and girls I work with to have 14 or more sessions per week (i.e. two to three times a day). But this wouldn’t be the case right before their next fight. Frequency, like the other six variables mentioned here, is context-dependent.

4. Progression

How do we progress the program over time? The concepts are few and the methods are many. Coaches often say that their profession is both an art and a science. The science part is the concepts, while the art is the methods used to prompt a desired adaptation that gets athletes closer to their goals. As long as your program is based on the concepts of performing a needs analysis to inform your goals, using progressive overload to balance stress and recovery, balancing SAID (specific adaptation to imposed demands) and LTAD (long-term athlete development), and maximize adherence, you’ll be likely to succeed.

5. Intensity

Lifting coaches often determine intensity by the percentage of an athlete’s one-rep max. Don’t go and add up all the intensities as you’ll end up with a crazy, largely meaningless number (and drive yourself nuts in the process). Instead, try to assign a percentage value to each day. Perhaps on Monday most of your athletes’ work was performed around 70 percent, while on Wednesday, they were working at 80 percent. From there, you can report intensity as a weekly average.

Volume and intensity typically have an inverse relationship. Say you asked an athlete to do 10 reps of an exercise one day and three reps another. On the first day, they’d have to use a lighter weight and lower percentage of their one rep max because of the increased volume, while on the second day they could go heavier and get closer to that max because the volume is now lower. You can’t do two reps with your one rep max – or that would be a misnomer.

6. Volume

Mathematically, volume = repetitions x sets. Such a calculation can help us better manage fatigue over time. We usually report volume as a weekly cycle for each exercise. Then you report that for each week in a mesocycle – let’s say over the course of eight weeks an athlete does 200 reps in week one, 300 in week two, and so on (that said, I wouldn’t typically advise varying volume by more than 10 percent each week, so don’t do that 200 to 300 jump without a specific reason). You can also record volume load, which is simply sets x reps x weight. A lot of S+C practitioners prefer this because it provides a more detailed picture. Suppose athlete A’s volume was 200 reps, but they only lifted 50 pounds for each rep. Meanwhile, athlete B performed the same 200 reps but with 100 pounds. You can see how athlete B’s volume total would be much higher.

7. Rest

Rest, intensity, and volume are more intertwined than the preceding four variables because they all influence each other directly. For example, if you reduce the rest periods, it will also likely reduce both the intensity and volume your athletes are exposed to. If you increase intensity, it will probably reduce volume too.

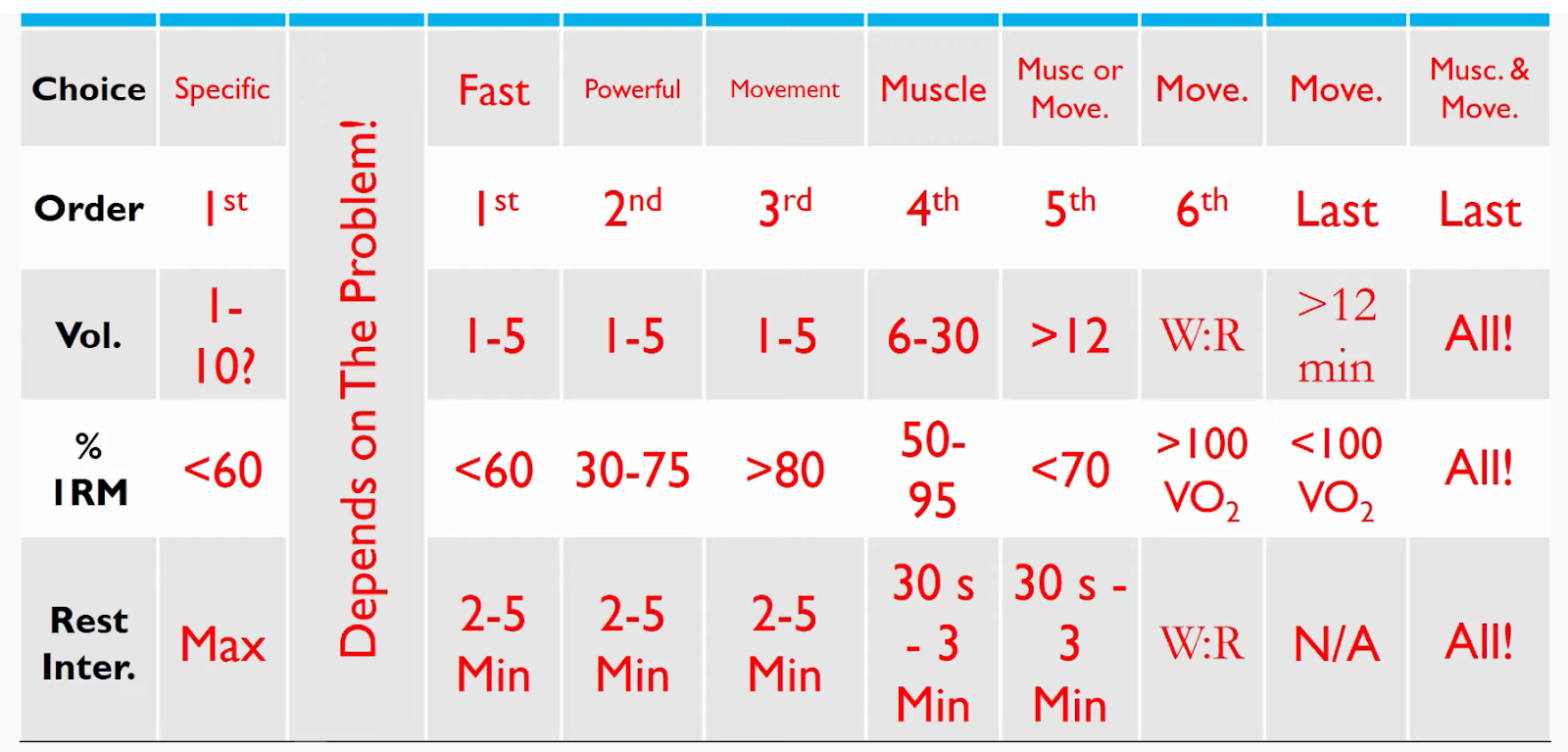

Below is a handy chart that gives an example of how you can change up the rest interval and four of our other variables:

Altering these seven variables like a music producer sliding and turning knobs on a studio mixing desk will prompt some kind of adaptation. Hopefully it’s the kind you’re looking for in your athletes. To make sure, you need to return to the two steps I mentioned at the start of this piece: your needs analysis and the goals it yields. Is the new program helping your athletes meet their goals and perform better in their sport? If so, then great, keep doing what you’re doing. If not, you can work through all seven variables again and make the necessary adjustments.

READY TO TRY TRAINHEROIC?

Our powerful platform connects coaches and athletes from across the world. Whether you are a coach or trainer looking to provide a better experience for your clients, or you’re an athlete looking for expert programming, click below to get started.

Want more training content?

More coaches and athletes than ever are reading the TrainHeroic blog, and it’s our mission to support them with the best training & coaching content. If you found this article useful, please take a moment to share it on social media, engage with the author, and link to this article on your own blog or any forums you post on.

Be Your Best,

TrainHeroic Content Team

HEROIC SOCIAL

HEROIC SOCIAL

TRAINING LAB

Access the latest articles, reviews, and case studies from the top strength and conditioning minds in the TH Training Lab