Energy Systems 101 Part 2: What Every Coach Really Needs to Know!

Coach Development | Sports PerformanceABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jonathan Mike

Jonathan Mike, PhD, CSCS*D, NSCA-CPT*D, USAW, NKT-1 is a currently a faculty member the Exercise Science Department at Grand Canyon University in Phoenix, AZ. He is also a Strength Coach, Writer, Author and Speaker and has competed in the sport of Strongman and currently beginning training in Jujitsu. He earned his PhD in Exercise Science at the University of New Mexico.

In Part 1 of this series, we thoroughly examined the truth about energy systems, their classification, specifics of each energy system, correct terminology used, and most importantly, how each energy system is interconnected and contributes to one another for energy provisions.

One of the more confusing aspects that continues to purvey is the role of fuel use during training, and even during recovery, and how intensity has large implications for these energy systems.

Many are discussing and even advocating basic programming ideas based on these systems without ever really thinking and knowing about how they work. This article will help set the record straight and examine the truth about energy systems.

Let’s get started with Part 2.

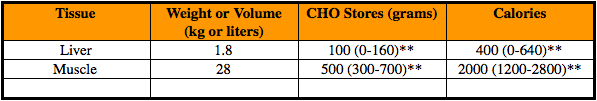

How the body converts food to fuel relies upon several different energy pathways, which was thoroughly discussed in part 1 of this series. When training, your body will use the carbs stored in your liver and muscle as fuel. We know this as glycogen stores (see table 1). These stored carbs originate from the foods you eat.

However, do we always train with our carb stores full? Not always. How does that affect performance? Well, just like many things training, nutrition, and physiology related – it depends.

Currently, a variety of nutritional methods are being used by lifters and trainees to augment carb stores in favor of using fat. These include ketogenic diets (24, 27, 41), lower carb diets (27, 35-39), and variations of carb cycling. Regardless of what type of method you may use, understand that different fuel sources and training intensity will not only dictate performance, but how that performance can be maximized throughout any given training session and competition.

Table 1: Sites and amounts of stored carbs in rested, moderately active 70-kg (154lb) man with 40% of body mass as skeletal muscle.

As indicated, the values coincide with a 154lbs man, probably 160lbs soaking wet, with a moderate amount of lean muscle mass. So, you can imagine how many grams of stored carbs and calories may be available for someone who is 230lbs, or 260, or 300 and has a lot of lean muscle tissue. The same goes for lean and strong women too, although they have less available storage compared to their counterparts.

Although there can exist an astronomical difference in stored energy fuel, it doesn’t mean you will:

- Become regularly depleted

- Expend all energy during training

- Need that amount of energy fuel all the time

How quickly glycogen stores might be depleted depends on the duration and intensity of the exercise and training session(s). Therefore, when it comes to fuel use during training, it’s all about that intensity and duration too.

// Fuel Breakdown 101

The relative utilization of fat and carbohydrate during exercise can vary enormously and depends strongly on exercise intensity. In the current training and nutrition culture, there is still a large majority of those who are die-hard carb fans, or die-hard fat fans, demonizing each other because of what they “believe” is the better fuel for training.

It’s not “what’s the best fuel,” but rather “when,” “how,” and “why” that matters most. It’s important to keep in mind that the fuel use and exercise intensity phenomenon was originally based on V02 max (7). However, since most of us care about lifting, the same information and physiology apply to your training as well.

During exercise, carbs and fats are the main source of fuel, not protein. Although protein can be used in the absence of low glycogen and long extended bouts of training from endurance exercise via glycogenolysis, carbs and fats are the main players. There is a mixture of fat and carbohydrate utilization during training, as the relative contribution of fat and carbohydrate utilization to total substrate metabolism is dependent on exercise intensity, exercise duration, diet, and training status (6, 8, 19).

Carbs

For simplicity, carbohydrates are stored in the body as muscle glycogen and liver glycogen…and circulating as plasma glucose. Interestingly, the liver has the highest concentration of glycogen (stored carbs), but by virtue of its size, skeletal muscle contains the largest store of glycogen (8). Glycogen provides an additional source of glucose besides that produced via gluconeogenesis (creation of new glucose from non-carb sources i.e. protein).

To help you understand, glycogen contains several glucoses, as it acts like a battery backup for the body, providing a quick source of glucose when needed and supplying a place to store excess glucose when glucose concentrations in the blood increase. Further, glycogen is broken down from the “ends” of the molecule, as more branches translate to more ends, and more glucose can be released at once for the liver and especially skeletal muscle during training sessions.

To keep things rolling, the breakdown of glycogen involves:

- Release of glucose-1-phosphate (G1P)

- Rearranging the remaining glycogen (as necessary) to permit continued breakdown

- Conversion of G1P to G6P (glucose-6-phosphate) for further metabolism

As you may recall from your bioenergetics or exercise physiology class, G6P can be broken down in glycolysis, converted to glucose by gluconeogenesis, and oxidized by another pathway (pentose phosphate pathway) that parallels glycolysis.

Fat

Fat is stored as adipose tissue (which has now been considered a hormone) and as intramuscular triglyceride (IMTG). In addition, some fat is present in the circulation as plasma free fatty acids (FFA) and as triglycerides (TG) incorporated in lipoproteins (biochemical molecules that contain both fat and protein, bound to the proteins, which allow fat to move in and out of the cell, and classified by their density). Common lipoproteins include VLDL, LDL, and HDL.

As you recall form part 1, fat oxidation requires oxygen. Because fats are long carbon chains, they are transported to the muscle mitochondria, where the carbon atoms are used to produce acetyl-CoA. In a four-step process known as the Beta-oxidation, fatty acids are broken down into acetyl-CoA to form CO2 and H2O. When using fat, triglycerides are first broken down into free fatty acids and glycerol (a process called lipolysis). The breakdown of fatty acid compounds go directly into the mitochondrion to produce ATP, as the oxidation of free fatty acids generate considerably more ATP molecules than the oxidation of glucose or glycogen.

An interesting side note, in order to transport fatty acids across the mitochondria, it requires what’s called a carnitine-dependent transport system, or shuttle (6, 13). In case you didn’t know, this is the location and main rationale for supplementing with L-carnitine, and why carnitine is a popular ingredient in fat-burner products (16, 23, 30).

// Fuel Use and Training Intensity

Now that you have a basic idea of fuel breakdown, let’s get started with the meat and potatoes. Keep in mind in these next several sections: fuel use and training intensity was originally built on V02 max. However, make no mistake, it 100% applies to lifting and resistance training.

As exercise intensity increases from rest to near maximal levels, there is a gradual transition to use more glucose and glycogen as the predominant sources of ATP (19). From a metabolic perspective in the mitochondria, more ATP can be produced aerobically from the breakdown of carbohydrate as opposed to fat. However, the main determining factors are exercise duration and training intensity. Other factors include age, training, and diet, but also gender, as well as hormonal factors (15).

In the post-absorptive state, the majority of the energy utilization comes from fat.

During low intensity exercise (25-50% V02 max, range of motion, activation and movement prep, or RAMP for lifting) the majority of energy production stems from lipid oxidation, as plasma free-fatty acid (FFA) oxidation provides most of the energy needed. At lower exercise intensities, most of the fatty acids used during training come from the blood (14). As exercise increases to moderate intensity (around 60% of VO2max) the majority of fatty acids oxidized appear to come from intramuscular triglyceride (14).

From a lab perspective, the technical term to measure energy expenditure and fuel use is Respiratory Exchange Ratio, or RER. The RER is a numeric index of carbohydrate and fat utilization based on a ratio of carbon dioxide produced to oxygen consumed. When using a metabolic cart, .7 is deemed 100% fat usage, .85 is a mix of fat and carbs, and .85 or greater up to 1.0+ is pure carb metabolism (19, 22). However, these indexes are not always straightforward as those with certain metabolic abnormalities (like diabetes) and trained athletes elicit different responses and do vary considerably.

During training, there is a dramatic increase in energy requirements because of the metabolic demand of working muscles. At greater intensities (i.e. > 60% V02 max, or completion of movement prep warm, and the first several sets of lifting, volume work, and heavier weights), the absolute contribution of fat oxidation reach maximum rates, thus transitioning energy production needed for exercise to carbohydrate utilization. Therefore, as the intensity of exercise increases, there is a significant reduction in lipid oxidation, and a significant increase in carbohydrate metabolism.

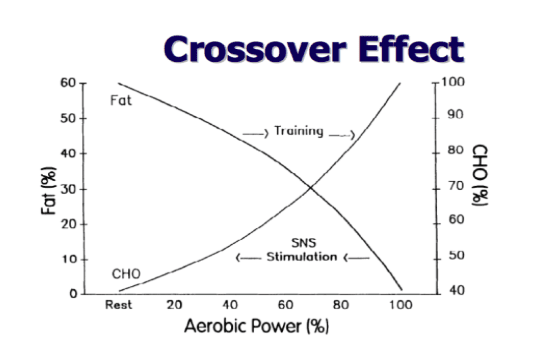

This phenomenon of the influence of exercise intensity and substrate utilization is termed the “Crossover Point/Concept.” This concept describes the crossover effect from fat metabolism to more prominent carbohydrate metabolism.

The Crossover Point is the intensity (expressed as a percent of V02 max, but also applies to heavy strength training) where fat and carbohydrate intersect when the energy from fat is reduced and carbohydrate increased. With increased exercise intensities, there are many processes that contribute to the increase usage of carbohydrates. These include:

- Contraction induced Glycogenolysis (breakdown of glycogen): As the intensity increases, glycogen breakdown occurs via specific pathways (calcium/calmodulin – for those who care), and epinephrine (adrenaline) catalyzing the formation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate, or simply cAMP, (a second messenger important in many biological processes and derived from ATP) which stimulates certain enzymes and glycogen breakdown.

- Fast Twitch Motor Units: As exercise intensity increases, many more fast-twitch muscle fibers are recruited, which are much more suited to utilize carbohydrates for the needed ATP production. As intensity increases, so does the glycolytic rate/flux, along with energy demand and force output (Olympic lifting, speed deads, max effort bench). Fast twitch muscle fibers are recruited in order to maintain/increase overall power output level for that specific exercise in addition to an increase in overall sympathetic nervous system activity.

- Epinephrine: Higher intensity exercise stimulates epinephrine production (adrenaline), which also enhances carbohydrate metabolism (19). As intensity increases, there is an increase in epinephrine, as epinephrine intensifies the contraction-induced rate of muscle glycogenolysis (breakdown of glycogen).

- Lactate: As intensity increases, the glycolytic rate also increases, along with the glycolytic enzymes. Thus increasing the formation of lactate. Lactate inhibits free-fatty acid (FFA) mobilization, and decreases uptake into the muscle. The increased lactate production, due to an increased proton accumulation inhibits hormone sensitive lipase, or HSA enzyme and FFA is not released into circulation and become trapped in the adipose tissue. These overall activities inhibit lipolysis and fat breakdown.

- Blood Flow: The reduction in fat utilization during high intensity training is also related to blood flow. Blood flow increases to the overall working muscle during training and during low intensity exercise, but during high intensity efforts, blood flow to adipose tissue is decreased and thus reduced fatty acid supply to the muscle. Meaning, at high exercise intensity, blood flow is directed away from adipose tissue so that fatty acids released from adipose tissue become “trapped” in the adipose capillary beds, and consequently are not carried to the muscle to be used.

Although these events are more complex than explained, you get the idea. These combinations of events all lead to a profound increase in carbohydrate metabolism and reduced lipid metabolism during high intensity exercise.

Before anybody goes nuts, there are some differences between carbs and fats with respect to energy provisions.

The primary advantages of stored carbohydrates in animals and humans are that:

- Energy is not released from fat as fast as from glycogen

- Glycolysis provides a mechanism of anaerobic metabolism (see part 1). This is important in muscle cells that cannot get oxygen as fast as needed)

- Glycogen delivers a means of preserving glucose levels that cannot be provided by fat.

Don’t misunderstand and take this out of context. I’m not saying fat is not used or cannot be used for energy, because it can. The highest outputs of the body are from anaerobic metabolism, which can ONLY run off either the phosphagen system or glycolysis. You can certainly train to get better at utilizing fat as it does provide some advantages, BUT, you will never see the highest outputs from an individual fueled only by fat. Bioenergetically it just doesn’t occur, as the maximal rate of ATP generation is slower than that of glycogen oxidation, and more than tenfold slower than that with creatine phosphate.

The critical part that nearly everybody misses is the RATE at which the body can produce energy during training.

It is just impossible to utilize fat to power fast/explosive movement, heavy low rep work, and moderate to high rep work. As I alluded to in part 1, a main disadvantage of anaerobic work is the production of other metabolic byproducts (example: H+ or protons) that prevent the sustained output over the course of training. From a training application, it’s best to train both (and preferably all energy systems) to their fullest extent.

Interestingly, a phenomenon that has gained enormous attention in recent years is the concept of metabolic flexibility, (3, 4, 9, 11, 17, 18, 21, 31, 34). Although a whole other topic, it’s the ability to switch from one fuel source to the next in a continuous fashion. Insulin is the substrate regulator, or main fuel selector switch, switching your body from burning mostly fat to mostly carbohydrate when needed (preferably during training periods).

So does this mean you need to eat a whole meat-lovers pizza before you train? No. But you do need to be cognizant of your training, nutritional habits, your individual responses to training, and how they vary depending on the type of training and intensity, duration, frequency, volume, etc. Interestingly, our bodies default metabolic state is one of fat oxidation, and insulin is simply the switch that turns it to carbohydrate metabolism when needed. However, many individuals and some athletes never switch fuel usage during training.

// Fats for Energy and Recovery

Since we just discussed the effect of training and intensity on fuel usage, your next question is “what about fat”? Are you burning fat during training or during recovery? And when does it occur, and how? After all, when it comes to fat loss, and getting lean, energy expenditure and a caloric deficit and a customized nutrition plan are the name of the game.

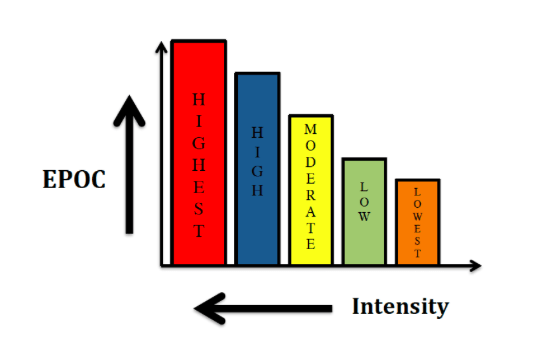

Isn’t it ironic that at low intensities (and long durations, long slow cardio, etc.) you achieve a greater relative percentage of calories used from fat storage vs. higher intensities. BUT higher exercise intensities attained from interval training, metabolic resistance training, training volumes, total body workouts, sprints, prowler sprints, sled drags, super sets, tri-sets, giants sets, complexes, etc. not only expend more energy, but also increase the body’s potential to use fats as an energy substrate to a greater extent than steady-state aerobic exercise and traditional resistance. This is due to increased up-regulation of enzymes responsible for beta-oxidation (process of fat breakdown).

Further, total caloric expenditure and lipolysis (fat breakdown) are greatly enhanced by higher intensity types of training, resulting in significant effects on fat loss (32).

Because of the complex nature of the human body, it continually adjusts its use of fat for fuel. However, as we know, substrate utilization is highly governed by many factors including hormonal regulation, enzyme activity, genetic influences, and these factors can change by the moment (29).

The fact is, many get caught up in how much fat they burn in a given training session. In order to obtain any significant effect and keep perspective on body composition, fat burning must be considered over the course of days, weeks, or months, not on an hourly basis (12), and not during a single training session.

Inevitably, the more carbs you expend during training, you burn more fat in the post-exercise period and vice versa. This elevated metabolic rate is the concept and application of excess-post exercise oxygen consumption (EPOC). This occurrence can burn additional fat and calories up to 72 hours post training, with intensity and duration (especially intensity) being the presiding factor (figure 2) (5, 20), as well as replenishment of creatine phosphate, the metabolism of lactate, temperature recovery, heart rate recovery, ventilation (breathing), and hormonal factors.

Further, EPOC has been notably observed after resistance training (25) resulting in a larger energy requirement after exercise to restore the contracting muscle cells to pre-exercise levels. EPOC has also been shown to be elevated for an extended period following eccentric training as well (10) due to the energy cost associated with protein synthesis and the repair and regeneration process. In addition, during the period of EPOC, fat oxidation rates have also been shown to increase (1, 2, 25).

Highly trained individuals and athletes have a much better ability to utilize fats and carbs during training (and even during recovery periods) and have a greater affinity to switch fuel usage for training and non-training days. Adaptations that enhance fat usage in trained muscles involve improving fatty acid availability to the muscle and mitochondria…and the ability to oxidize fatty acids. These adaptations lie largely within endurance training, but in recent years have transitioned over to lifting and other competitive sports.

From a nutritional perspective, this has to do with the concept on fat adaptation.

“Fat adaptation” is a protocol in which mainly endurance athletes consume a high-fat, low-carb diet for up to 14 days while undertaking their normal training (both high volume and high intensity) (40). It can also be used as a stand-alone dietary strategy or can be followed immediately by a period of CHO restoration, consuming a high-carb diet and tapering for 1–3 days. There exists a lot of controversy regarding the specific approaches to take, and which fuel source people believe to be the “best.” Many feel that fat should be the main preferred fuel source over carbs for training, as some believe it enhances performance to a greater extent while others, and some scientific evidence, says otherwise.

This of course is highly variable for each person, population (examples: diabetes, fat loss clients, athletes), sport, individual responses to training and nutrition, goals, and genetics. There is no one-size fits all approach.

Due to these physiological occurrences to training discussed in this article, you can now begin to understand the idea and real life applications of how energy intake can influence substrate oxidation, the importance of nutrient timing and its effect on muscle strength, hypertrophy, and protein synthesis. All of these things govern and effect the large implications of sports performance.

Are you a better coach after reading this?

More coaches and athletes than ever are reading the TrainHeroic blog, and it’s our mission to support them with useful training & coaching content. If you found this article useful, please take a moment to share it on social media, engage with the author, and link to this article on your own blog or any forums you post on.

Be Your Best,

TrainHeroic Content Team

HEROIC SOCIAL

HEROIC SOCIAL

TRAINING LAB

Access the latest articles, reviews, and case studies from the top strength and conditioning minds in the TH Training Lab