Getting Lifters Ready to Excel in Competition (Be Your Best: Part 3)

Coach DevelopmentABOUT THE AUTHOR

Sean Waxman

Sean is the head coach and owner of Waxman’s Gym. He’s been a professional coach for nearly 25 years, a national-level competitive weightlifter, and a graduate-level student of kinesiology and biomechanics. Since opening Waxman’s Gym in 2010, Sean has developed two top-ten finishers at the World Championships, a World University Championship Silver medalist, a Pan Am Championship Silver medalist, and two Pan Am Championship team members. In addition, Sean has developed more than two dozen national-level weightlifters with three National Champions and seven national medalists. Moreover, Sean’s lifters have produced four American records, nine international medals, and nearly two-dozen national medals. Sean has also worked with CrossFitters of all levels including Regionals and Games athletes. When not developing competitive weightlifters and CrossFitters, Sean works with athletes of all skill levels from a wide range of sports to help them develop great skill, strength and power. Sean also has a great passion for helping other coaches learn to teach/coach weightlifting. Sean is currently a Director on the Board of USA Weightlifting, a USA Weightlifting Lead Instructor for Coaching Education, and the former President of the Southern California chapter of USA Weightlifting.

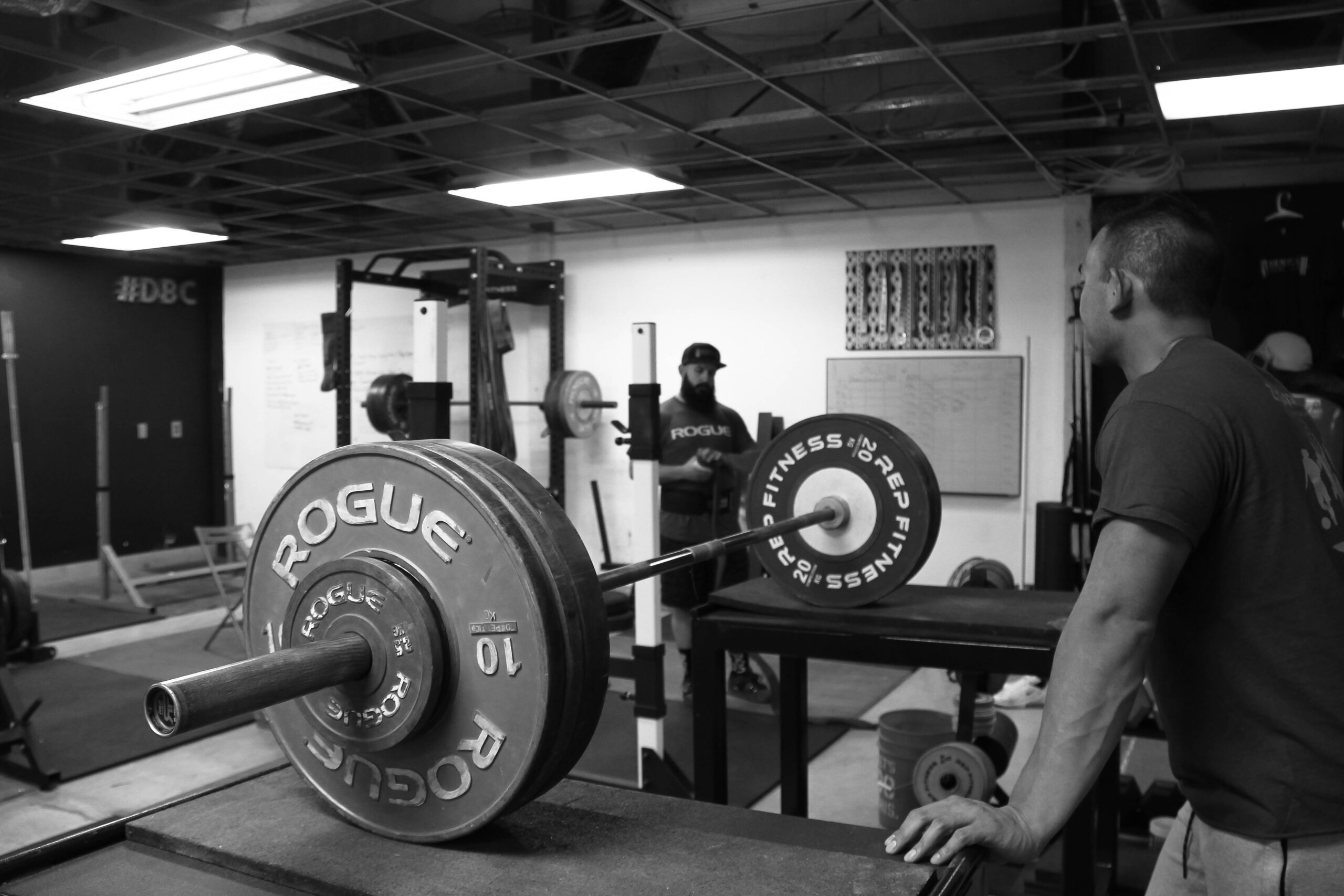

I just got back from weightlifting nationals and all our athletes met their goals. In the immortal words of John “Hannibal” Smith from The A-Team, “I love it when a plan comes together.” But while the end result was satisfying, the meet was merely the culmination of a long, hard journey. The road to excelling in competition begins long before an athlete ever sets foot on the platform and requires the creation and execution of a multi-phase strategy for each and every one of our lifters.

Over the years, I’ve come up with some tried and true approaches that we use at our gym, which trickle up to our competitive team. They reflect my framework for how I believe the snatch and clean and jerk should be taught and how we implement accessory lifts. I start with the end in mind. This doesn’t just mean setting targets for each lifter, but also what I want the perfect lifts to look, feel, and sound like based on their current speed, technique, ability, and future potential. Then we work backwards and use a parts-to-whole method to get to that destination. The development of each athlete goes through three phases, each of which might take a different amount of time to work through depending on the individual. We have to “chunk” the information and then deliver the chunks in sequence.

// 4 phases to get lifters ready to excel in competition

Your Title Goes Here

Your content goes here. Edit or remove this text inline or in the module Content settings. You can also style every aspect of this content in the module Design settings and even apply custom CSS to this text in the module Advanced settings.

Phase One: Beginner (Key Emphasis: Concept)

When someone’s just starting out, it’s crucial that they come to understand the concept of what the Olympic lifts truly are. We’re usually starting with a blank slate (see Phase Four: Wild Card for the exception to this rule), which provides the opportunity to create some initial proficiency and get things right from the get go. At this stage in their development, the athlete is usually consistently inconsistent. This means that they make different errors at different times because they’re still getting their technique dialed in. The goal at this point is to reduce the variance of the errors so that we can hone in on repeated mistakes and address them.

The use of accessory work also has to be purposeful. For example, we squat not just to improve strength, but to also increase the speed with which the lifter comes out of the bottom of their clean. Beginners are exposed to a wide variety of exercises and I want them to make the connection between each of these and their Olympic lifts. When they understand why they’re doing something, we see a greater training affect.

Phase Two: Intermediate (Key Emphasis: Coordination)

Once the range of errors has been narrowed and the athlete is consistently showing better technique, they progress to the intermediate phase. Now it’s time to improve the coordination of the full movements. We’ve succeeded in reducing the number of mistakes to a mere few, and now our focus shifts to trying to reduce the magnitude and frequency of each. As a coach, it’s my job to not just identify the most common errors, but also decide which are the most profound ones. We call these source errors because they’re at the root of other ones. Once we have found a couple of source errors, we can help the athlete make a lot of progress by fixing them.

Phase Three: Advanced (Key Emphasis: Strength)

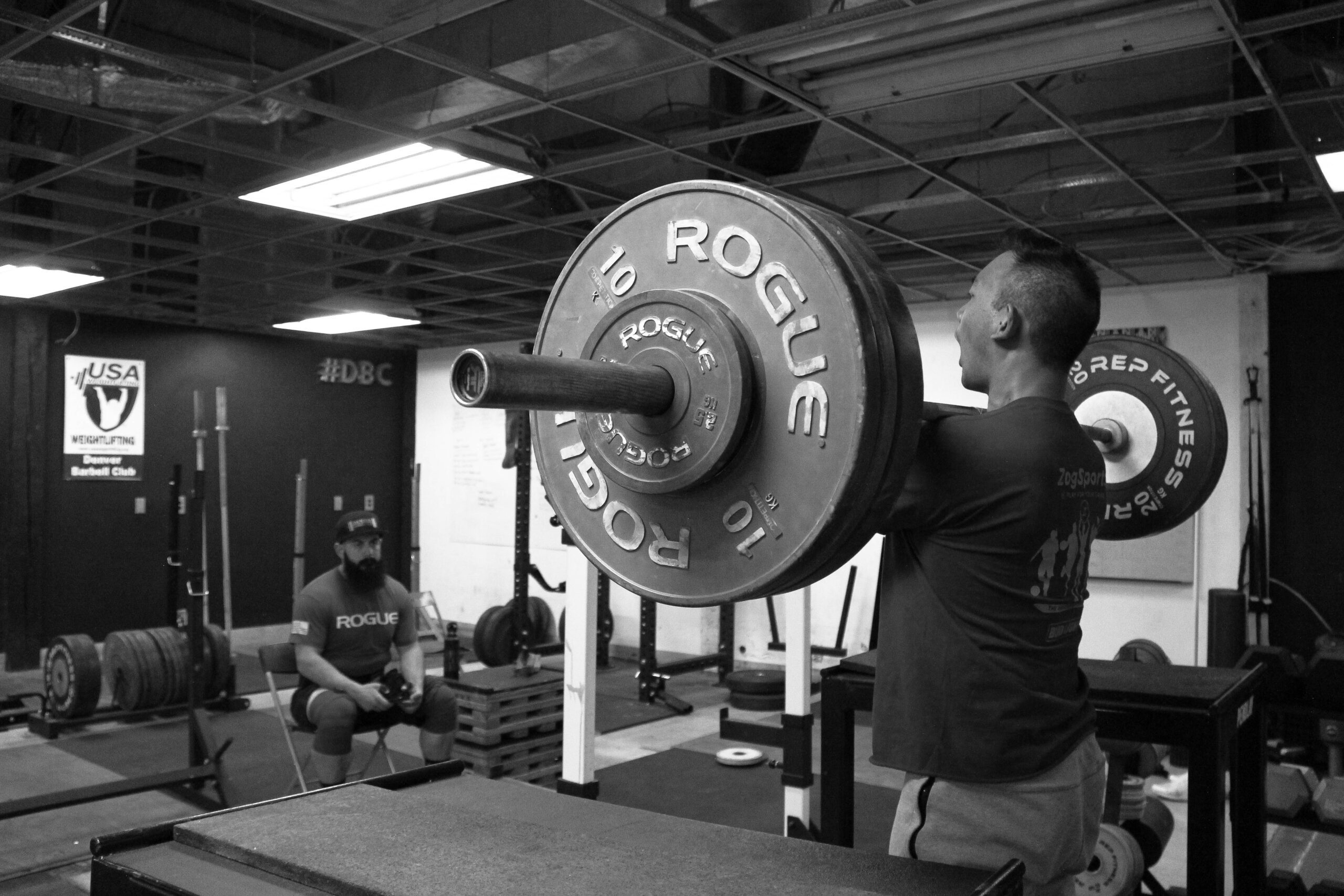

Once a lifter has become consistently consistent, we move on to the advanced stage of their training. Earlier in their development process, they cannot do what they’re supposed to with regularity because they lack understanding of the key concepts and don’t have the requisite coordination to perform the snatch and clean and jerk consistently. When they become more advanced, they make mistakes because of a lack of strength at some point in the lifts. Our problems are now typically weight or capacity-driven ones. The goal is to figure out their threshold and then raise it with just enough stress at the right time, but not one iota more so the athlete doesn’t get too beat up.

When they’re at the beginner and intermediate levels, we can add more volume and intensity because they’re not as close to their maximum capacity. But they’re now at the point where they’re using most of their ability, so I have to be mindful of giving them just enough of a stressor to prompt adaptation, and no more. It’s not a question of getting them to do as much as they can, but rather as little as possible to get the desired outcome.

Phase Four: Wild Card (Key Emphasis: Concept, Coordination, or Strength)

There’s a fourth stage for athletes in which the initial focus is unclear. This typically applies to lifters who have come to Waxman’s Gym with some prior exposure to the Olympic lifts, but haven’t had the benefit of going through the three phases described above in a systematic manner. As a result, they may have issues with concept, coordination, and/or strength. It’s up to me to determine which issue is holding them back the most. Where is the one place that I can focus my energy to get the biggest bang for the buck? Once I’ve zeroed in on this, I can determine the overriding purpose for the athlete’s next training block and can plug them into the correct part of the three-phase framework. It’s a matter of making an educated guess and then acting upon it. If the lifter doesn’t get the results we want, then I go back to the drawing board and try something else.

// the meaning of makes and misses

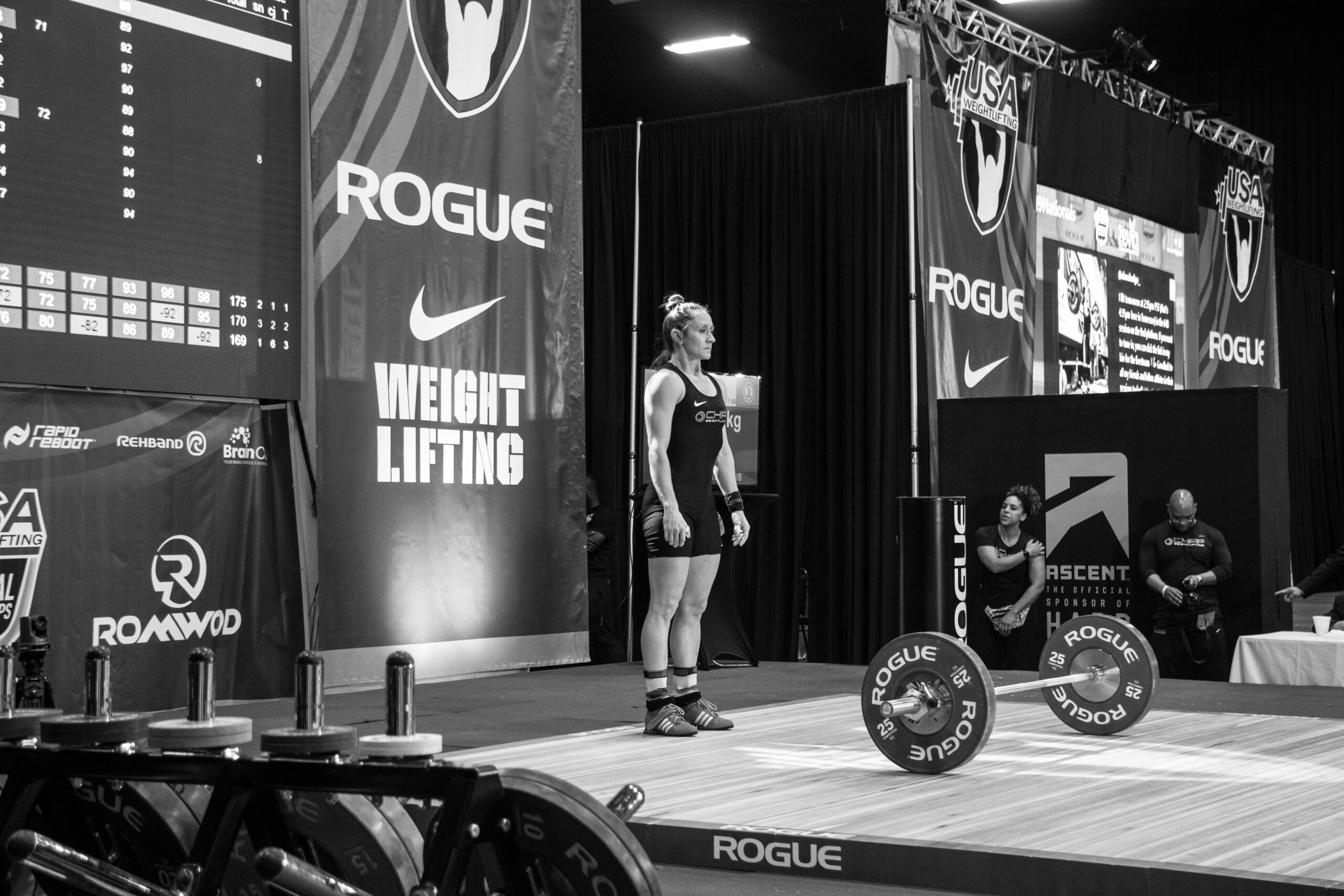

A big part of my process that’s woven into all three phases is being ever-mindful of makes and misses. In competition this comes into sharp focus, but in any meet a lifter will only have a handful of attempts. Assuming that they participate in five competitions a year, with six attempts in each, they have 30 opportunities to perform in 12 months.

Whereas if we consider their preparation, a beginner might have around 8,000 reps in a given year, divided into five, nine-week training blocks or cycles with meets and breaks in between each. For the sake of simplicity, let’s say that this is broken down into 4,000 snatches and 4,000 clean and jerks. How many of these they make or miss will largely determine how well they perform those 30 competition lifts. If an athlete misses 10 percent of their attempts in training, that’d be 400 clean and jerks and 400 snatches missed, or 800 in total. That’s an awful lot of reinforcement of faulty technique!

The more times the neurological system runs a specific motor pattern, the more likely it is to default to this, particularly when the performance becomes largely automatic, as it is during competition. Should an athlete miss 800 total lifts, they’re grooving a bad pattern over and over again, which is bound to show up in what happens on the platform come competition time.

Then there’s the psycho-emotional impact of that many misses. Psychologically, the biggest thing I can provide you as your coach is confidence. This is directly tied to developing a habit of success in training. If all someone knows is succeeding day in and day out, they’ll continue to achieve it in the heat of the moment. Whereas if they’ve been conditioning to fail over and over, they’re much more likely to come up short in a meet. That’s why it’s imperative that we obtain a high make-to-miss ratio.

This doesn’t mean that we artificially inflate the number of makes. Far from it. I don’t count a rep that’s slow or sloppy. It needs to look like it would in competition to count. If necessary, I’ll adjust the intensity, reduce the volume, or increase the rest between sets to get the speed, technique, and coordination we’re after.

// let’s fight!

Going into a competition, every lifter is aware of what their goals are. But I don’t want them to think while they’re on the platform – they just need to do what needs to be done. This means that I use very few words. What I say depends on the personality of the athlete, but the tonality of my voice is always the most important factor. If someone is more aggressive by nature, I’ll adjust the cadence and tone of what I’m saying to elicit more of an adrenaline bump. Whereas if someone’s quieter or nervous, I’ll speak more slowly and softly. Before they touch the bar, I might give a simple cue based on something we’ve been working on in training, give them some encouragement, or say nothing at all.

At nationals recently, we had two lifters who missed their second clean and jerk attempts. So it was vital that they made their third ones. They both nailed it, and for one of our female lifters, that make boosted her up from fifth place to second. A single lift was the difference between medaling and not. When you get to this stage in a meet, the only thing I’ll say to encourage an athlete is, “Let’s fight!” At the end of the day, it’s not about how strong someone is or how technically proficient they are. It’s a question of them showing incredible heart and spirit to stick their last lift. That being said, what happens on the competition platform doesn’t occur in isolation. It’s the results of weeks, months, and years of practice and preparation. When it comes to getting results, everything matters.

Are you a better coach after reading this?

More coaches and athletes than ever are reading the TrainHeroic blog, and it’s our mission to support them with usefull training & coaching content. If you found this article useful, please take a moment to share it on social media, engage with the author, and link to this article on your own blog or any forums you post on.

Be Your Best,

TrainHeroic Content Team

HEROIC SOCIAL

HEROIC SOCIAL

TRAINING LAB

Access the latest articles, reviews, and case studies from the top strength and conditioning minds in the TH Training Lab